Taft mountains hold 'secret' of missing cemetery

The mountains surrounding the legendary saloon town of Taft, Mont., holds a silent grip on its deceased residents. As the massive fires of 1910 swept through the canyons of Mineral County, the blaze took the town with it, including the cemetery. A cemetery with wooden markers which turned to ash and disappeared. Now, nearly 110 years later, the search is on to find the 72 buried souls lost to a century of forest growth and erosion.

The search originated from historian John Shontz, who was interested in writing an article about the St. Paul Tunnel at the East Portal, located two miles up the road from Taft. From his research he found out about the missing cemetery, and a search party was put together which included Shontz, his son Nick, Forest Service Archeologist Erika Karuzas, Superior Forester Bruce Erickson, and volunteer Steve Waylet along with Montana PBS Producer Gus Chambers, and production assistant Nick Turnbull.

“There’s 72 souls sleeping somewhere on that hillside, and it could be fun to find them,” Shontz said before the search began.

For several hot Saturday afternoon hours on Aug. 11, the group scoured the steep terrain, hoping to find depressions in the soil or other items which may identify the old burying ground. Shontz is a retired lawyer from Helena, and has always had an interest in the history of trains and railroads. He frequently writes articles for the Milwaukee Railroad Historical Association, and was looking into writing one about the St. Paul Tunnel on the famed Milwaukee “Route of the Hiawatha.” The tunnel is now the starting point for a popular bike trail maintained by Lookout Ski Area Resort just seven miles east of the Idaho-Montana border.

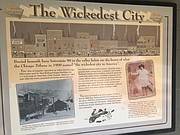

CONSTRUCTION STAR-TED in 1906 on what was to be the biggest tunnel project on the Milwaukee system, spanning 1.66 miles. The railroad built a camp to house approximately 1,500 men who worked on it. Down the creek the town of Taft was born and sported 27 saloons and 500 prostitutes. It was viewed as a “wicked” town and represented the last of the lawlessness of the Wild West. Since it was 80 miles west of Missoula, the sheriff could do little to monitor the town and the “law-of-the-land” often resulted in gunfights and murder.

In addition to those killed in Taft, others lost their lives to disease and accidents while building the tunnel. The railroad built a 75-bed hospital and contracted four doctors and a handful of nurses to run it. Edith Schussler was married to one of the doctors and chronicled her time in Taft in a 1956 book, “Doctors, Dynamite and Dogs.” It was through her book that Shontz discovered the cemetery and began checking into its location.

He checked through Forest Service records and could not find any mention of it. Interstate 90 runs directly over Taft and the Montana Department of Transportation also did not have any records of a cemetery being disturbed in the Taft area. Karuzas said the Forest Service had assumed the cemetery had been covered by the interstate when it was constructed. During his research, Shontz also contacted the Mineral County Historical Society, which knew about it but did not know where it was located.

From records, the cemetery was located near the hospital. However, the building was sold in 1909 for $35 and torn down for its lumber. Shontz also talked to Greg Bentley, who works at the East Portal of the Hiawatha Trail, and said he had seen the cemetery and could make out some of the depressions of the graves. Giving Shontz further clues as to where to look.

Along with the search party was Gus Chambers, who is producer for Backroads of Montana. He said that it makes for an interesting segment for the show, which airs on Montana PBS.

“We like to do stories on small out-of-the-way places and Taft qualifies for that. Even though the town itself is buried under Interstate 90, a lot of people know about the town and its nefarious history,” he said. “This story is like an onion with many layers. There’s the history of the town, the archeology in searching for the cemetery, and the present people interested in finding it. John Shontz’s enthusiasm for the subject and Erika’s willingness to help offers a level of credibility. This isn’t an amateur project, but a professional endeavor for the record books.”

ANOTHER CLUE to its location lies in the history of the workers themselves. The majority of them came from Montenegro, a small country in former Yugoslavia. Their leader, referred to as the “King,” had recruited nearly 1,000 unemployed miners and brought them over to help build the tunnel. In a dispute with a foreman on the Milwaukee Railroad, the “King” was killed in a gunfight and buried in the cemetery.

Shontz made the assumption that since he was an important man, perhaps they had marked his grave with a stone, rather than a wooden marker. He is fairly certain it is located on Forest Service land and after the Saturday search, Karuzas said they may have found two or three locations that may be gravesites. But without any real evidence, “I am leery to say we found them,” she said.

One possibility is to have cadaver dogs come into the area and possibly locate the graves, but that would depend on funds and availability. Regardless, she will not reveal the exact location if found. “Per the National Historic Preservation Act, it is my duty to protect our cultural resources,” she said. “If we say where they are located, it could lead to the graves being disturbed and potentially robbed. Out of respect to those interned there, we will try to protect their final resting place.”